Wallace Stevens as seen by David Hockney

Thanks to all sixteen poets who came to the workshop on 'Poetry in Three Dimensions' - an introduction to book arts - at the Poetry School last weekend. We had some fascinating discussions about the relationship between poetry and design, and it was great to witness everyone's enthusiasm for getting stuck in and making their own books.

We looked at different presentations of Wallace Stevens' work by the artists David Hockney and Helga Kos. As a young man Hockney produced a print series in response to Stevens' long poem The Man with the Blue Guitar (itself inspired by a painting by Picasso); Stevens' late poems, set to music by Ned Rorem, feature in Kos' artist's book Ode to the Colossal Sun. Kos describes her three-volume work as 'a third, visual stratum to Stevens' poems and Rorem's music' and I've no doubt that in time this setting - which won the accolade of Best Dutch Book Design in 2004 - will be considered as iconic as Hockney's.

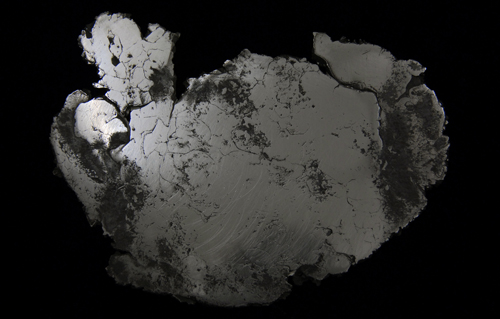

Wallace Stevens as seen by Helga Kos

The class drew inspiration from these artists' books to make three hand-bound volumes to present their own writing. As the binder Keith Smith writes:

'Bookbinding at its ultimate realisation is not a physical act of sewing or gluing, but a conceptual ordering of time and space. It is not sewing but structure of content that ties together the pages of a book. Binding must begin with the concept of text and/or pictures.'

You can see images of Anne Welsh's beautiful setting of her poem 'Arran Jumper' over at her blog Library Marginalia, and the photos below show work-in-progress on Elizabeth Bell's poem on the sea deity Sedna, and Zakia Carpenter's ingenious thread-typography.

Pochoir stencilling